Consumer robotics have stagnated

Despite a few glimmers of hope, consumer robotics has changed little over the past 5 years

In 2019, Amazon launched the Amazon re:MARS conference, effectively creating a public version of Jeff Bezos’ invite-only annual MARS (Machine Learning, Automation, Robotics, and Space) event at a California resort. At his party, you might rub shoulders with anyone from actor Mark Hamill to computer scientist Stephen Wolfram, or casually observe Adam Savage playing table tennis against a robot or catch Michael J. Fox taking in a falconry session. If that wasn’t enough to keep you entertained, maybe watching Festo’s flying robotic manta rays float autonomously through the air or watching Spot, the robotic dog from Boston Dynamics prance across the grounds would do the trick.

The Alexa Prize

Alexa was born from Jeff’s desire to have a Star Trek computer that could have natural conversations with humans. He’d already achieved part of that dream by having Alexa devices bring “ambient computing” to the home, and getting them to do much more than just control music or turn on lights or set timers was the next step to making that dream a reality. To accelerate the progress towards that goal, he created the Alexa Prize, a university competition to build an Alexa-based chatbot that could converse “coherently and engagingly with humans on popular topics and news”. A prize of $1M was up for grabs for any team that could build a chatbot that could do this for 20-minutes with a 4 out of 5-star rating from the human. I helped launch the program in 2016 as the technical lead.

The university teams were using a special version of the Alexa software development kit (SDK) that wasn’t available to the general public, and were granted generous use of AWS resources to train and run their models. Even with that head start, a 20-minute coherent and engaging conversation with a robot was (and still is) a hard problem to solve. In fact, the winning team that year was from the University of Washington, and had an average rating of 3.17/5 and an average conversation duration of 10 minutes and 22 seconds.

I worked closely with the 16 university teams, helping them use the AWS infrastructure to build data pipelines and train models. They each had different methods of creating conversational AI, but in 2016 none of us knew about the transformer — the architecture behind the chatbots we know today — and Google’s famous paper describing it had not yet been published.

But what I noticed when working with these teams is that they had plans beyond just an ambient Star Trek computer. Most of those plans included some sort of consumer robot. I saw demos for emotional support robots, children’s toys, personal tutors, mobility aids. I began to see signs of a future of “embodied AI”, and I didn’t think it was too far away.

Amazon re:MARS

I’ve been fascinated with robots since I was old enough to read. When my mom found me in the stacks of the public library reading medical books about eyes, I told her I wanted to build eyes for robots. As a 7-year old living in a rural Texas town, my options were limited. So three+ decades later when I was asked to come be the technical lead for the new re:MARS conference, and to build a robotics “lair” filled with robots in the expo hall of the Aria Hotel in Las Vegas, it was an easy yes. By 2019 I’d seen enough robotics progress from both the university teams and in our fulfillment centers that I thought we were about to have a robotics explosion. The promise of sidewalk delivery bots, robots that folded laundry, and robots that could serve drinks and make dinner seemed to be just over the horizon.

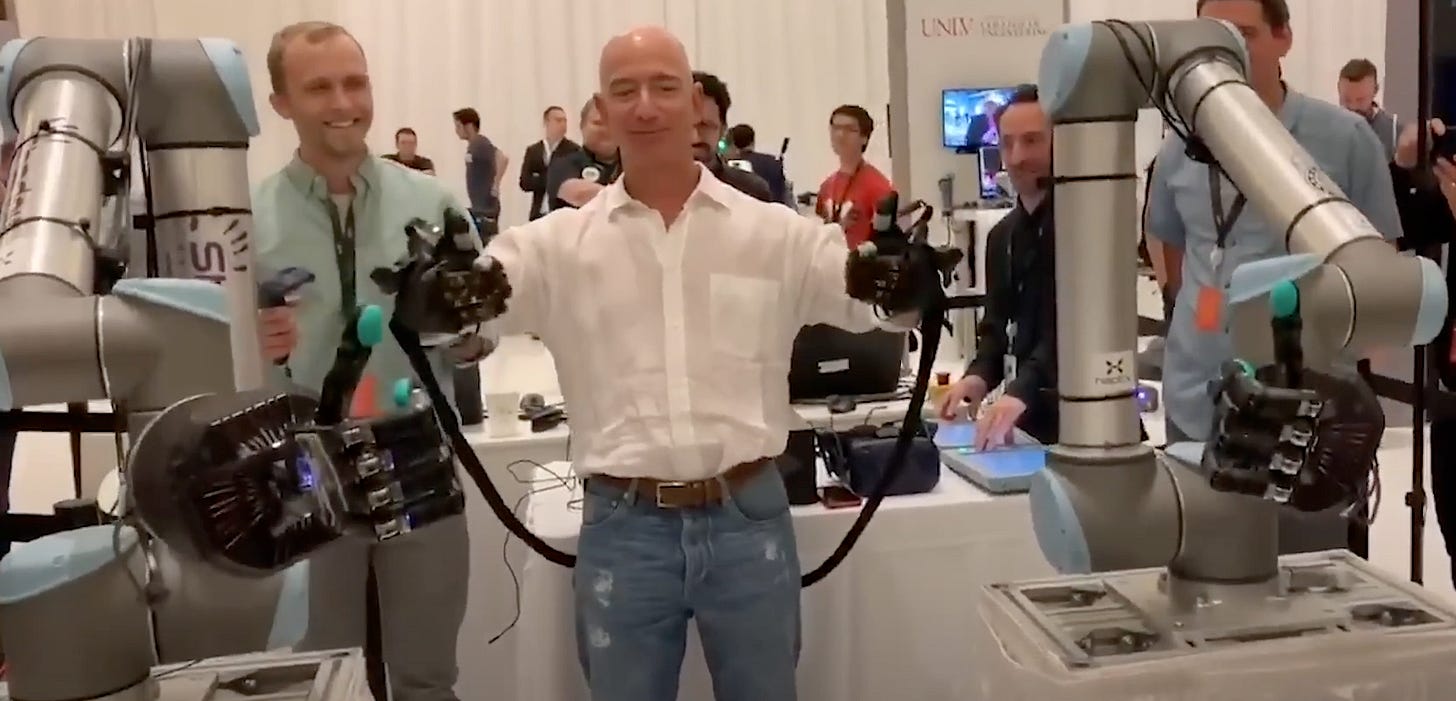

I used my academia connections and filled the lair with robots from CMU, the University of Michigan, BYU, Harvard, Berkeley, and more. We had DARPA robots that navigated tunnels, insect-size flying drones, robotic snakes that searched for survivors in collapsed buildings, and humanoid robots from UNLV. We built a miniature version of an Amazon shipping center that had robots delivering packages to a conveyer belt, while robotic arms from KUKA and Fanuc moved boxes around with ease. I designed a workshop that let attendees program with the Robotics Operating System (ROS) to control a Roomba vacuum cleaner with their voice in a simulated house. A prominent roboticist at Amazon told me, “grasping is probably the hardest thing in robotics right now,” so I found SynTouch, who were working on solving that. Together with HaptX, they’d created a telerobotic system with a haptic glove that could let a remote user “feel” objects from afar. One of their goals was to let operators on earth “feel” objects on the International Space Station. That exhibit was probably Jeff’s favorite.

Fast-forward to 2025

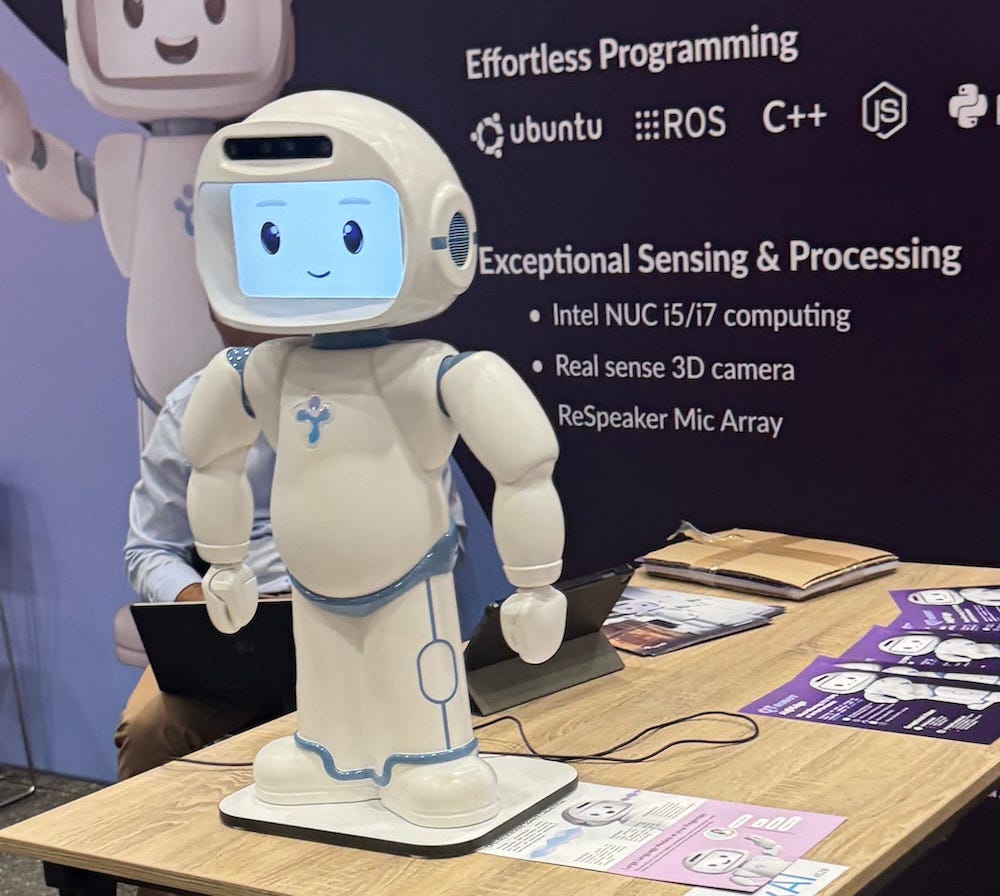

Two weeks ago, I attended the UN AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva, Switzerland. One part of the conference I was looking forward to was their robotics exhibition, and seeing the advancements made in consumer robotics over the 5+ years since I’d left that world behind. LLMs had largely solved some of the big hurdles Alexa Prize teams had faced in understanding the wide ranges of human intent, and Vision Language Action Models like Google’s RT-2 can not only understand human intent but give robots “sight” and a set of instructions they need to navigate in the physical world.

Instead of being wowed, I felt an immense disappointment at the lack of progress in consumer robotics. It was as if someone had time travelled back to 2019 to pick out robots and bring them to the future. From what I have seen, progress has slowed to a crawl.

Why have consumer robotics stagnated?

Hardware...is hard. There are orders of magnitude more people that can sit down at a computer and build a useful app, game, or tool. Some will even build the next multi-billion dollar company. For every Steve Wozniak building the next Apple Computer in their garage, there are thousands more in their garages trying to build the next Stripe, AirBNB, DoorDash, or new indie game you’ll see at the top of mobile app stores soon. Writing a “Hello World” program in Python or JavaScript might only take a new programmer an hour or less while following a straightforward tutorial. But if you try following the annoyingly-convoluted instructions of the ROS2 documentation for robotics and you’re looking at a few hours, minimum, to move a turtle around the screen. And that’s assuming you already know enough about operating systems and are comfortable doing a lot of the initial work from the command line.

And let’s say you spend a few weeks creating a virtual prototype of a robotic lawnmower, like I did. You’re finally ready to try it out in the real world, but as you expected, moving from bits to atoms costs a lot of money. The servos, actuators, gearboxes, and stepper motors you used in your robotics simulator are no longer free, and sometimes difficult to find. The barrier for entry is high, and margins are thin.

Consumer robotics are not a priority

If the barrier for entry and cost to develop weren’t enough, the main reason consumer robotics have stagnated is because consumer robots are not a priority.

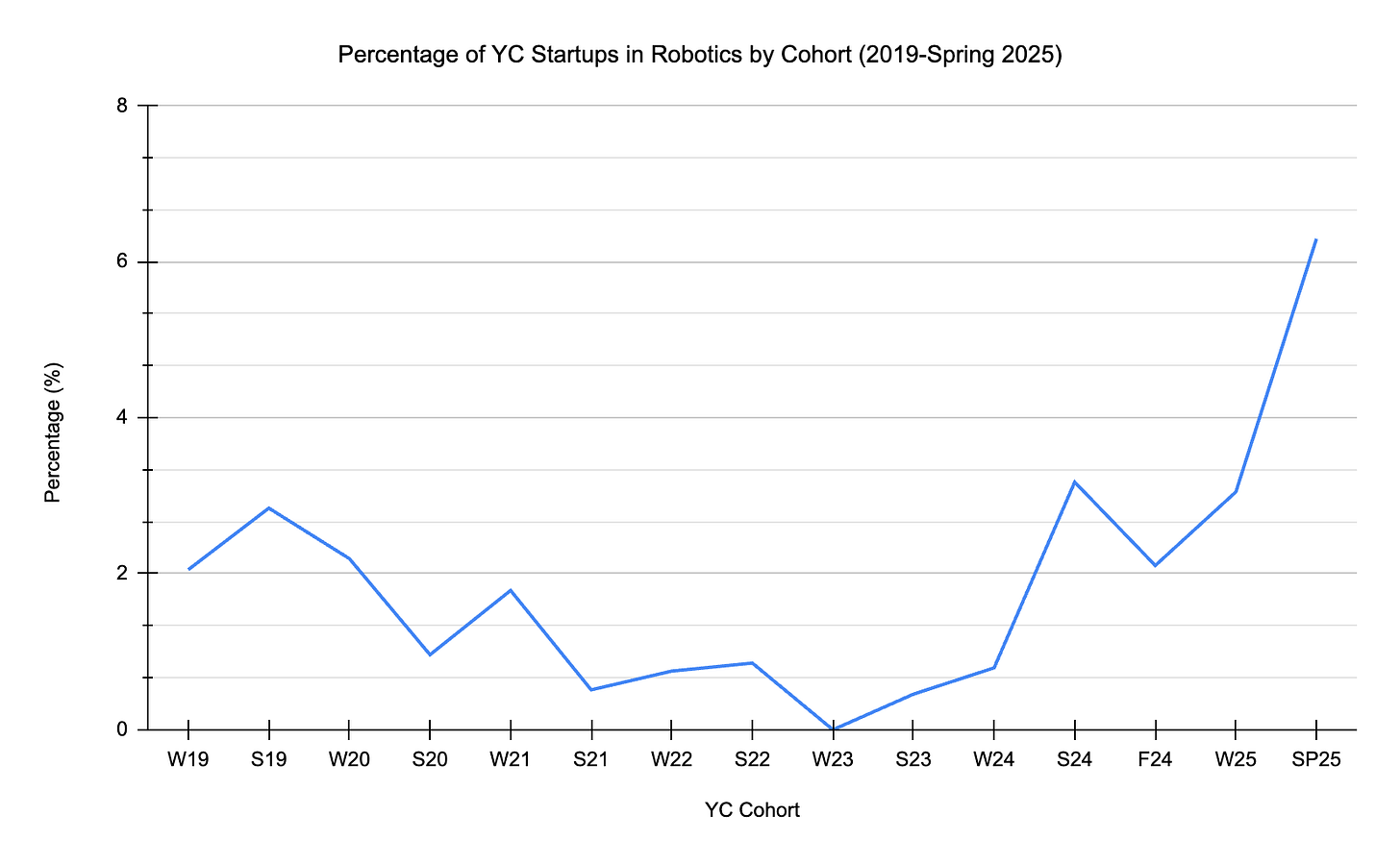

When I’m doing research on technology trends, one of the first places I look is at what companies Y Combinator (YC) has funded and admitted into their startup accelerator, and what the primary purpose of those companies is. Take a look at the number of YC companies involved in robotics since 20191. There are only roughly 56 companies out of 3567 that were working on robotics over that timeframe, and fewer still working on consumer robotics. Over the past 15 cohorts, 1.6% of YC companies were actually working on robotics. Compare that to agentic AI companies, who have nearly 10x the representation at 15.8%; a number that will undoubtedly balloon over the next few years.2

Of course in this span we had a “black swan” event in COVID-19 and the “ChatGPT moment”, both of which affected progress on more than just robotics. And this graph doesn’t take into account the amount of robotic experimentation happening in China, or Japan’s long history of varying successes with companion robots like Lovot. But for the foreseeable future, the majority of investment dollars will go towards software-based AI, not robotics.

So it stands to reason that here in the west, the first signs of progress we’ll see will not be in robots that can cook or fold laundry, but rather in the areas of mobility or robotic companionship, especially for the elderly.

For mobility, I watched a promising presentation at the AI for Good Innovation Factory while in Geneva. Glidance is aiming to replace the walking cane with a self-guided mobility aid for people that are blind or have low vision. For companionship, we’re already seeing a deluge of software-based AI companions like Character.AI and Replika that have flooded the app stores, and there is interesting research being done on the effects on well-being of human-chatbot relationships. And I’ve heard anecdotes from people that use Alexa who tell me their elderly parents and grandparents treat Alexa as a companion they have conversations with. A companion that never gets annoyed when they constantly ask if it will rain today or what the time is. As assistants like Alexa and Siri continue to evolve and add in the features we see in ChatGPT or Claude, these scenarios will be more common. The conversations will be more meaningful, and longer. They’ll remember things. They’ll check in on you to see if you’re okay. After that, the money will follow, but not until the newness of generative AI has waned a bit and the windows of research and investment expand beyond to include consumer robotics again.

I don’t think there will ever be a “ChatGPT moment” with robotics, where suddenly everyone is either talking about them or has them in their home. The closest we might get is if an affordable (sub $2K) humanoid robot, like a stripped-down version of Tesla’s Optimus for example, creates a revolution in home robotics like IBM and Apple did for home computing in the 1980’s. But based on the rate of change I’ve seen over the past decade, that dream is probably still another decade away.

Note, don’t be fooled by just typing in “robot” to filter the companies. There are several companies with the word “Robot” in their name that don’t make actual physical robots. Also, I did not use data from the Summer 2025 cohort because at the time of this writing the list may be incomplete.

This number is obviously skewed over this time frame. Between 2019-2022 only three YC companies were working on agentic software. To give you an idea of how new it is, the word “agentic” is still likely to be identified as misspelled by most browsers and word processors in 2025.