We're not vibe coding enough

Despite some naysaying, there are real benefits to vibe coding more.

Viberank is a leaderboard that ranks developers by how much money they spend on Claude Code, Anthropic’s AI coding agent1. For the month of July 2025, the top 5 participants spent an average of $9.6K apiece; that’s basically $115K/yr to have an AI assistant help them build things. To put that in perspective, 2025 Glassdoor estimates the median annual salary of a developer with 1-3 years experience to be $105K/yr.

Spend any time in the comments section of a Hacker News post on vibe coding and you’ll find plenty of naysayers that point out the perils of letting AI code everything for you. And to be fair they make a lot of good points, especially when it comes to how important it is to really understand the systems these agents are building, and not launching AI-generated code blindly into the wild.

What Viberank doesn’t track is the other AI coding agents besides Claude Code; many of them letting you do so on generous free tiers. Viberank is a good indicator of the direction things are headed, but it's barely scratching the surface of how widespread AI-assisted coding has become.

I’ve been experimenting with tools like this since early 2024. These days, I’m evaluating and experimenting with any of a half-dozen agentic coding tools2 at any given time, maxing out my daily free-tier limits on several. Over the past two weekends, I’ve spent 8-10 hours in total vibe-coding three different proofs-of-concept:

A WhatsApp bot that lets you create and manage interactive polls with your friends. Asked Claude 4.0 to poke holes in the plan after I got a quick version 1 up and running. It told me Telegram bots were probably better because there were fewer restrictions and more customizations over WhatsApp. I agreed after reviewing its evidence, and had it convert it to a Telegram app. This one took the longest at least 4 hours, but some of that was jumping through hoops on Meta and Twilio to get the WhatsApp version working.

A service called Mixtape, where you can SSH into a machine to get a daily “mixtape” of songs around a certain theme. I knew curating a daily list of songs was going to be tough, but I figured I’d use AI for that. The demo came together quickly, which is a good thing, because it was only after connecting to it for the first time that I realized how bad this idea was: you can’t play songs in the terminal (if you even have the licenses or links to them) and you’ll run into concurrent connections limits with SSH pretty quickly if you want to scale.

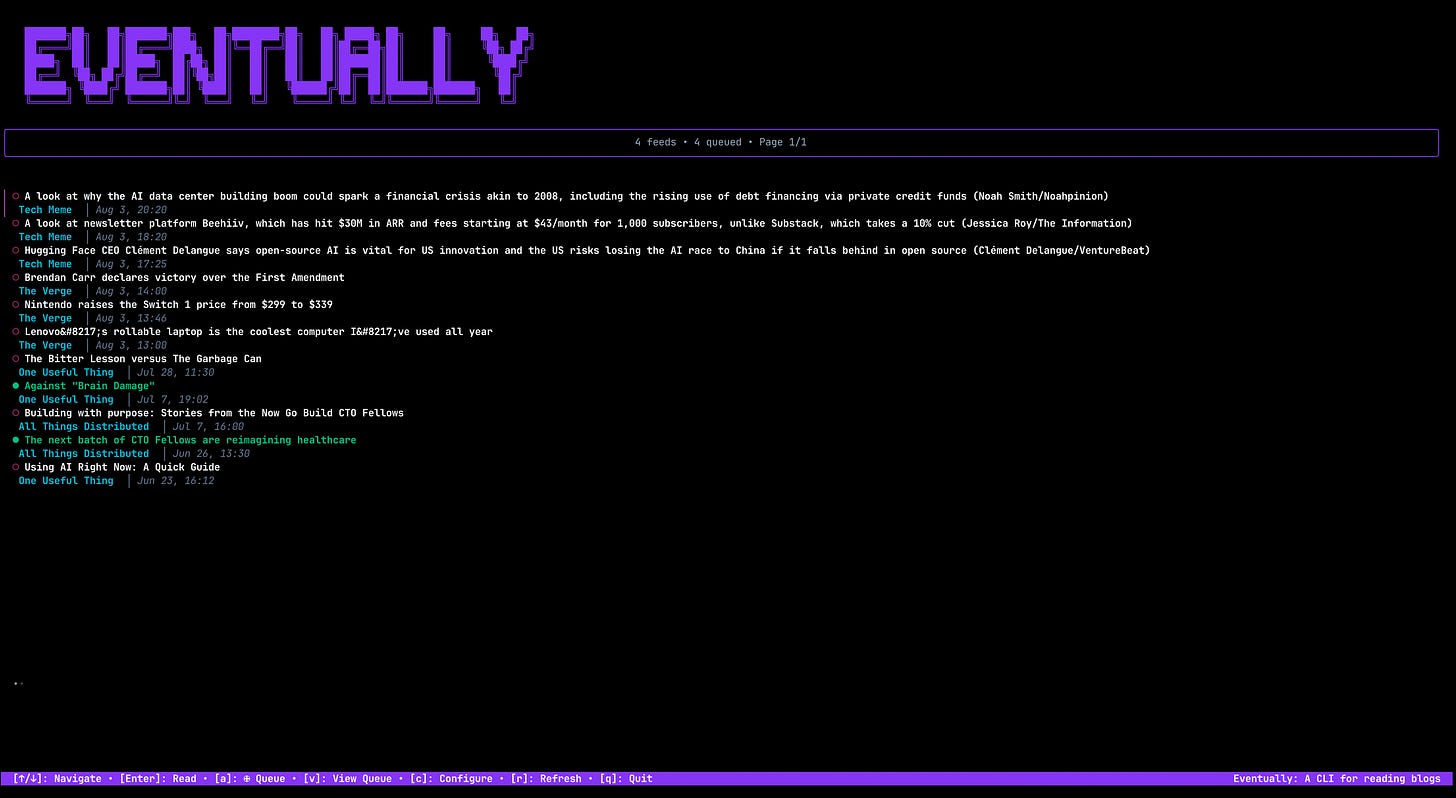

A command‑line tool called “Eventually” for browsing, queuing, and reading blog posts directly in your terminal. This one took less than 90 minutes, and a lot of that was tweaking little things like colors or layout. Turns out these AI coding agents still have a lot of work to do on that front.

Why this matters

None of these apps really matter. They work, but they’re hardly useful. No one is asking for these things. I don’t know of anyone besides me that cares about having a bot to manage polls sitting in a WhatsApp group, or anyone looking to abandon their music client to drop into the command line and ssh into a box to get a list of songs they can’t really listen to. And who really cares about reading a blog post (with no pictures) in the terminal? But here’s what I gained from those 8-10 hours:

I learned a few new things. I know a little more about messaging apps and why Telegram may be more useful than WhatsApp for robust bots. I know how to configure a Twilio sandbox and phone number now, and point incoming messages to a Lambda function URL. I used Terraform (for the first time) to deploy my infrastructure to AWS. I know more about Go (the language the two command line apps were written in) than I did the week before. All this in a day’s work over two weekends, thanks to vibe coding. Counterintuitively, vibe coding helped me discover new things faster despite hiding most of the code from me.

Just as importantly, I proved to myself these apps aren’t worth spending a lot of time on. Normally when I get an idea, I get excited about what it might turn into and jump right in. I need to see it living and breathing on a screen before I can see all of its shortcomings. I spend weeks, or months, and even a couple of times — years — building something that almost never materializes into anything people actually want. But sometimes you need to see the thing before you can know the thing. And now I’m able to reach that conclusion faster than I ever have before.